Monday, January 30, 2012

Focus on Weight Class Weaknesses

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Nick Diaz - Smarter than the Average Bear

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

The Core is Like a Garden Hose

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Snorkel Training for MMA? Rad or Fad

Wanderlei Silva is an intense human being. The way he fights is intense. The way he looks is intense. And his conditioning regimen is intense. Another way to describe Silva’s conditioning is innovative – he wears a snorkel. Besides looking badass, there is supposed science behind this training tool. Firstly, don’t think that snorkel training is a good idea just because Wanderlei does it. Rookie move. Many athletes are successful despite their training methods, not because of it. Time to take a deeper look…

At high altitude, there is a decrease in oxygen saturation (known as hypoxia). A lot of fighters train at high altitude because after roughly ten to twenty days, the body adapts to these conditions by increasing their Red Blood Cell mass (which increases the oxygen’s blood carrying capacity). Snorkels create a similar ‘hypoxic effect’, minimizing the amount of oxygen you will take in each breath. This however, WON’T have the same affect as altitude training. You may spend 15-20mins training with a snorkel, which is a lot different to living day in, day out at high altitude. The benefits of snorkel training exists elsewhere… When you breathe out, some of the air remains in the snorkel. This air will have high levels of carbon dioxide. This means that your next breath will have more carbon dioxide than normal, and your blood carbon dioxide levels will increase. This will make your training bout a lot tougher, and will probably improve the ability to remove carbon dioxide from your blood.

Some controversy does surround this method. Firstly, as a fighter, one of the first rules you learn is breathe through your nose. As soon as your mouth is open, your chin is a bigger target, and you are more likely to be knocked out. Encouraging breathing through your mouth during hard bouts of work may not be the best habit to develop. Secondly, if you use a snorkel without being highly trained, your training bout will not be that effective. It will make you feel gassed early, and the power output during your training bout will be greatly diminished.

So, we now know that snorkel training won’t cause the same adaptations as altitude acclimatization, and that breathing through your mouth might not be the best thing to encourage. Being innovative with your training isn’t always a good thing. Save the snorkel for snorkelling!

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

Conditioning to Prevent Fatigue, or Conditioned to the Feeling of Fatigue? PART II

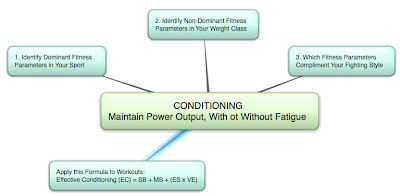

We came up with the following equation for conditioning:

Effective Conditioning (EC) = SB + MS + (ES x VE)

1. Strength Base (SB): We rarely have fighters that ask us for a strength training program, but we start almost every fighter on one. We convince them easily by asking ‘Would you rather be strong and conditioned? Or weak and conditioned?’ Having a foundation of strength means you have the potential to be more powerful, and trying to maintain the greatest power output is the ultimate goal of conditioning (with or without fatigue).

2. Metabolic Specificity (MS): Understand the work: rest ratios and the intensity of the working periods. The majority of your conditioning should be spent developing the predominant energy system of your sport. For combat sports, this usually means the anaerobic energy systems (ATP-PC System and Glycolytic System). Might be time to drop the long-distance runs…

2. Voluntary Effort (VE): apply Dutch kickboxing mentality and perform every rep with 100% effort. In combat sports, movements are typically power-based. Remember, intensity and volume have an inverse relationship. Having a high rep range looks good on paper, but if you can’t maintain your power output, it doesn’t look good anywhere else.

3. Exercise Selection (ES): consider the dominant movement patterns of your sport, and which muscle groups are involved. Compound movements work best because they integrate many muscle groups, eliciting a greater heart rate response (which is what conditioning is all about!).

Here is a basic conditioning template for you to experiment with. We have made sure the exercises are high cadence, explosive in nature and make you use your whole body. Choose the rep ranges based on your fitness level, and start with 3-4sets. Make sure you apply the formula above!

Why do we perform skill-work at the end?

You aren’t training to get better at burpees, you are training to get better at fighting. The goal of conditioning is to create the worst possible environment, and then try to remain technically sound. Have sharp strong boxing combinations when you don’t think you can move your arms. To shoot for a takedown when you can barely stand. To be conditioned to the feeling of fatigue, and still be able to perform technically.

Check out MMA Fighter Alex Chambers perform a conditioning circuit at RT HQ:

Monday, January 16, 2012

Conditioning to Prevent Fatigue, or Conditioned to the Feeling of Fatigue? PART I

The goal of almost every fighter is to have great conditioning; to never feel the sensation of fatigue in a fight. But is this what we are really training for?

We define conditioning as:

‘ The ability to maintain a given power output with or without fatigue ‘

The last part of the definition is probably the most important. Everybody thinks that a well-conditioned fighter doesn’t get tired. Not the case. A well-conditioned fighter is able to perform for whatever the prescribed time period is. If you finish a fight and still have a ton of energy left over, that isn’t necessarily great conditioning, it may just be poor management of available energy. If a sprinter runs 100m, isn’t tired, but finishes in 15seconds, that doesn’t sound like good conditioning…

We have fighters who begin training with us, and are exhausted when they hit 75% of their Max Heart Rate (MHR). We ask our fighters to give us a Rating of Percieved Exertion (RPE) after each round. It isn’t uncommon after a few months of training for a fighter to report a lower RPE, with a higher heart rate; maybe 85% MHR this time. The athlete has become conditioned to the feeling of their arms and legs feeling like lead, their heart beating more times than they can count, and their brain feeling like it’s going to pop out their ears. Sure they have had some physical adaptations take place (increased lactate threshold, increase in anaerobic enzymes, increased substrate storage, etc), but the athlete has now become conditioned to performing with fatigue present.

In our last article, ‘Why you need to hit the gym...’, we suggested that improvements in movement economy and the law of diminishing returns means that it becomes harder and harder to improve your fitness. This is where supplementary conditioning comes into play.

Check out the video below, and in our next post we will give you a basic conditioning template, discuss some basic guidelines, and explain why integrating skill work is so important.

Friday, January 13, 2012

Why you need to hit the gym...

Let’s take a look at what’s going on…

Martial arts is about learning how to move your body efficiently. Efficiency in sport means that your movement economy allows you to maximize the output with minimal input. With sports mastery, technique takes over fitness, and your refined movement patterns have a lower energy cost than before. This means that to get the same feeling as the first time you ever performed 10 continuous kicks, you may now need 50. (Translation: less energy necessary for more work)

The law of diminishing returns (taken from economics) states that exercise will cause the body to adapt to a specific stimulus, and eventually, as the training stimulus continues to increase, the fitness gain will become smaller and smaller. This means that increasing to 20kicks from 10kicks may be a strong training stimulus, but when another 10kicks is added, the training stimulus won’t be as strong as the 10kick increase before. This will continue for every 10kicks, and eventually, there won’t be much difference between 120kicks and 80kicks. (Translation: more volume necessary for a gain in fitness)

So now that we need less energy for more work, and we have accommodated to a training stimulus, we now need more volume for a gain in fitness. This means your normal 60minute training session may need to increase to 120-180mins. Not everybody has the luxury of training for this amount every day (due to work, family and a social life for the few fighters who have one), and there is a chance of the athlete developing volume-induced overtraining (which should be avoided at all costs).

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Sport Specific Supersets

When you hear superset, you normally think Bench Press followed by Cable Fly’s. The technique is normally used to increase the muscle’s time under tension, and subsequent microtrauma which will be a more potent stimulant for hypertrophy. Muscle size is rarely a training goal of a fighter who has a weight-restriction, but don’t rule out the pairing of exercises just yet…

There are two schools of thought when it comes to strength training improving sporting performance. Both have the same ultimate goal: to have the greatest transfer of training effect. Some argue that the exercise must closely resemble the movement encountered in the athletes sport. Others suggest that by practicing the sport concurrently with strength training, the body will learn to use the newly developed strength in the sporting movements.

We are firm believers of the latter (due to differences in the angle of resistance, differences in the phases of the movement, and the fact that there are so many different movements in BJJ/MMA), The implications are that performing uppercuts with a 15kg dumbbell may not necessarily make you a knockout machine.

What does this have to do with supersets? Complex sets were popularized by strength coaches in the eastern bloc, and involve pairing a Strength exercise with a Power exercise. The theory behind it is that because power exercises typically use low external loads, its hard to activate all of the motor units which make up a muscle - the strength exercise will activate the high threshold motor units, making them more likely to fire in the power exercise (1).

Time to kill two birds with one stone… Sporting movements typically have high velocities. A punch, for example, is performed explosively. It would make sense with the information we know, that using a punch after something like a bench press would be a specific way to improve punching power (because we have pre-activated the muscle prior to the power exercise – punching). Not only that, studies have shown that by performing sporting movements immediately after a strengthening exercise, the rate at which it is integrated into sport is quicker (2). Ben Johnson was known for performing heavy squats immediately before sprinting (word on the street was he was squatting a heavy set of three before he ran 100m in 9.79secs)

Check out the video below of a few examples of some sport-specific supersets:

REFERENCES

1. Siff, M.C. (2003). Supertraining (6th ed.). Denver, CO: Supertraining Institute.

2. Cronin, J., Marchall, R.N., McNair, P.J (2001). Velocity Specificity, combination training and sport specific tasks. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 4, 168-171

Saturday, January 7, 2012

Crossfit - The Jack of All Trades

“I’m not trying to be the best at exercising” – Kenny Powers

We are often casually asked whether our training system is ‘like Crossfit’, and to avoid a drawn out conversation, I hesitantly say ‘Yes’. Although our exercise selection may seem similar to what you see in a Crossfit workout, our training methodology is different. Before you think we are jumping on the Crossfit hate train, this article was not written with that intention. In fact, Crossfit deserves praise as it has introduced ‘functional movement’ to the masses, and has done a great job in collaborating information from various fitness professionals from different fields.

Let’s begin by asking yourself this question: “If I was a competitive basketball player, would I start playing soccer to improve my basketball performance?” On paper this doesn’t look that bad, as speed and agility are present in both sports, and both sports are intermittent in nature. BUT, what about all that stuff that doesn’t cross over. Isn’t that wasted time? Surely training to improve your vertical leap, specific agility drills and structured energy system training is time better spent.

What does this have to do with Crossfit you say? Let’s first take a closer look at what Crossfit is all about. Crossfit has identified ten fitness parameters, and aims to develop competence in each fitness parameter. The goal is not to specialize. The goal is fitness. Training sessions are centred around a ‘Workout of the Day’, where individuals aim to perform the most amount of work in a specified time, or aim to complete a prescribed workout in the fastest possible time. Sports have individuals compete against each other and a winner is defined by objective means. By this definition, Crossfit is a sport.

If you answered ‘No’ to the question above, you are acknowledging that there is probably a more efficient way to improve your sporting performance than by integrating another sport into your training regimen. Sports typically have two dominant fitness parameters, and aiming to improve these fitness parameters will have the greatest transfer of training effect into your sport.

MMA demonstrates this perfectly. Have you ever seen a belt-holder who aims to be competent in Judo, Wrestling, Sambo, BJJ, Boxing, Muay Thai, Savate and Taekwondo? Just like the select fitness parameters you should be focusing on, MMA fighters invest most of their time in Wrestling, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Boxing/Muay-Thai for the greatest chance of success.

Stay tuned as we reveal the REAL connection between Strength & Conditioning and Combat Sports…